On August 25, 1923, a strong young man emerged from the gates of the Warsaw prison in Mokotów. Before that, Yitzhak Farbarowicz received civilian clothes, old worn shoes, a kilogram of bread and a ton of moralizing.

Soon he got out of the suburb into the central streets of the Polish capital. Poland could not recover from the First World War and the subsequent battle for independence. Because of the raging inflation, the money saved over the years of imprisonment was enough for exactly two days. Friends from the Warsaw gateway came to the rescue and borrowed a small amount. These same old acquaintances immediately suggested Yitzhak to go into business together, but Farbarowicz did not want to return to the criminal craft after long years in prison. His path lay to the east, to his native Wizna on the Narva River, where the former prisoner went to ask his brother for his share of the inheritance left by his father.

But the brother was adamant: “You still have younger sisters who will need money much more than a reveler like you”.

Failing to find a livelihood, Farbarowicz returned to the criminal path once again.

On January 4, 1924, Yitzhak Farbarowicz, who took a short walk in the wild, was brought to the Bialystok District Court. The very last sentence in his life was, at the same time, the most severe – 8 years of strict regime. As an incorrigible recidivist, Farbarowicz was soon transferred from Bialystok to a prison in the town of Ravich.

The Ravich prisoner was known to the police for a long time: he began his “career” even before the war, was familiar with the prison at the age of 15, the criminal nickname – “Nakhalnik” (Impudent) – was given by criminals for the incredible audacity of the robberies and thefts.

Usually such a track record was characteristic of a person from the very bottom. However, in the case of Nakhalnik, things were different. Yitzhak Farbarowicz, born in June 1897 in the town of Vizna, between Lomza and Bialystok, was the long-awaited firstborn of the mill owner and grain merchant Shmuel Farbarowicz and his wife, Khai-Yospa.

At the age of five, Yitzhak , after a special send-off in the synagogue, was solemnly taken to the cheder. Young Farbarowicz did not like cheder, despite the fact that he was one of the best students.

In 1910 it was time to leave home. The father took his son to Lomza, where in those years the yeshiva, known throughout Poland and Lithuania, was located. The youngest of the 200 students of the Lomza Yeshiva initially liked to study. However, the constant torment over the Talmud soon exhausted Yitzhak so much that he could no longer think of anything but a respite and home walls.

Soon his parents decided to transfer him to a yeshiva located in the town of Bykhov, Mogilev province.

Farbarowicz’s cousin studied in Bykhov, who also planned to become a rabbi. Parents sent their son to a distant Belarusian province, hoping that a pious relative would give their firstborn the brains. However, the result was diametrically opposite, burying the Farbarowiczs’ hope for a brilliant future for their son.

The next blow for Itzchak was the death of his mother. The widowed father immediately sent his unlucky son a letter, in which he refused to help him with money, and even advised him to think about his own life.

Yitzhak began to earn his living by studying Yiddish and Hebrew. Despite a growing reluctance to study at the yeshiva, he remained there until the spring of 1913. A few days before Passover, Yitzhak collected his simple belongings and went home.

Thanks to the help of the local community, a poor schoolboy got a job as a teacher of Yiddish and Hebrew in one of the respectable suburbs of Vilno with a salary of 50 rubles. The life of the young teacher began to improve until he fell in love. His chosen one was incredibly beautiful Sonya, whose father paid Yitzhak for private lessons. Farbarowicz, completely lost his head, was already thinking of proposing to Sonya, until he accidentally found out that she was simultaneously having an affair with a student, a French language tutor.

From grief and anger, the rejected Yitzhak decided to take revenge on his counterpart. Not finding a rival in the villa, the young man took his gold watch and wallet, and, without saying goodbye to Sonya and her parents, went to the station. The next day, at one of the stations, a guard drew attention to a suspicious Jew. Then everything happened at lightning speed: the gendarmes, transportation to the Lomza prison, the investigation.

In November 1913, a former teacher, who was sitting in cell No. 93 of the Lomza prison, was brought to an important police rank. The Pole sitting opposite Yitzhak reproached him for immoral behavior, but, referring to his old friendship with his father, promised to close the case. Later it turned out that the father had contributed 200 rubles for the early release of his son.

Yitzhak had a hard time at home. He was not even allowed to share the table with the whole family. An attempt to steal money again and escape to the vastness of Russia ended in failure - the father noticed his son's preparations and at the most crucial moment caught up with the boy, beating him almost to death.

This continued until the beginning of 1914. At the family council, where even distant relatives were present, it was decided to send Yitzhak to his father's brother, who after marriage became the owner of a large prosperous bakery and grain trading company. In a bakery located in one of the provinces of the North-West Territory, the scapegrace worked until the beginning of May 1914, until he contracted encephalitis.

Somehow recovering from his illness, Yitzhak decided to go back to Wizna. He never returned home, but got a job as an assistant to a local cabman. This acquaintance became fatal. The cabman constantly rubbed himself among the dark personalities and soon asked Yitzhak to give a ride to his acquaintances. He began to deliver the thieves to the addresses almost every day, taking them from the appointed place with the loot.

For this, in addition to a fixed payment, he received every little change from the thieves' spoils. Soon, a love line was added to the thieves' romance. He could no longer think of anything else but Hanka, the younger sister of the leader of the gang. It was difficult to surprise a girl with such a reputation, so Yitzhak decided to finally join the gang and show the beautiful lady what he was capable of. From the first day, he began to participate in numerous thefts from apartments and shops, gaining the thieves' qualifications and honing the corresponding experience.

For some time he had to lay low. Having somehow made peace with his relatives, in April 1915 Nakhalnik got a job in a bakery, where he managed to work until August, when the Lomza province was occupied by German troops.

As an experienced driver, Yitzhak soon offered his services to a German military engineer who was working on the restoration of the destroyed bridge over the Narew River. The German lived at the Farbarowiczs’ house, and an officer's canteen was also organized there. Participation in joint meals with the Germans became a new stumbling block and caused a final blow to Yitzhak ’s family relations.

Yitzek decided to seek his fortune in Germany. He quickly spent the money he had accumulated at home on cards and women. Farbarowicz decided to fix his precarious financial situation in a way that was already familiar to him. With a former “colleague” from Poland and two local thieves, Nakhalnik burst into a store on the busiest street in Berlin. They took the cash desk, everyone was able to leave with the loot, except... Farbarowicz, who was loaded with things. On May 16, 1916, a bandit found himself within the walls of the famous Berlin prison Moabit.

A month later, the unlucky hijacker was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Nakhalnik would have sat in a foreign land for many years, but after a two-month stay in prison, a young girl unexpectedly visited him. On a date, it became clear that the street lady was the sister of an accomplice who had escaped from the police. The special handover turned out to be “English hair” – special strings for sawing grates – which fellows in the shop sealed into a large sugar head. Attached to the tool was a note detailing the escape plan.

After celebrating his miraculous liberation, on September 19, 1916, Farbarowicz returned to Poland and settled in Warsaw. Two weeks later, in spite of the promise given to God, people and himself to stop, Yitzhak again got to work.

The looting and revelry continued until November 9, 1916, when, during his visit to Lomza, Farbarowicz was accused of stealing German military supplies. Never, even years later, the impudent admitted this offense. Farbarowicz was beaten with mortal combat and even taken to a mock execution. In the end, it turned out that the Germans suspected the young Jew not only of burglary, but also of spying for the Russian army.

On October 28, 1917, Farbarowicz was unexpectedly released from the Lomza prison. Another girlfriend led Farbarowicz into a gang of “veterans”, or horse thieves.

Until May 1918, Nakhalnik managed to appear in numerous thefts in Vilno, until he again ended up in the Lomza prison, which he knew well. Together with his cellmate, Farbarowicz made an attempt to escape, but it did not work.

At the beginning of 1919, Nakhalnik was given 6 years in prison for the thefts he committed. Leaving his attempts to escape, Yitzhak Farbarowicz entered the Polish school established at the Lomza prison...

Prisoners' leisure was often brightened up by a book, but, unfortunately, Nakhalnik did not find books in Hebrew and Yiddish in the library. At the age of 22, he began learning to read and write in Polish, which was not taught in traditional Jewish schools.

Simultaneously with his studies, Yitzhak Farbarowicz tried to write himself. He knew Polish, Russian and German fluently, but at that time he could write fluently only in Hebrew and Yiddish. Finding himself in the middle of 1918 for a long time in solitary confinement, Farbarowicz began to write poetry. However, writing materials were strictly forbidden to prisoners; verses had to be scratched on the wall with a fingernail and memorized.

On November 18, 1919, Nakhalnik was transferred to a prison in Warsaw. Thanks to his thieves' and prison experience, as well as the enormous physical strength shown immediately after arriving in the cell, Farbarowicz quickly gained authority.

Working in a bakery and acting as an arbitrator in controversial situations between prisoners, Itzek continued his self-education in Mokotów.

Within the walls of Mokotów, Nakhalnik even established an exchange of books between cells, for which he repeatedly sat in a punishment cell. The guards did not allow prisoners to read more than two books a week, believing that this distracted them from work and, in general, they had to suffer from what they had done, and not have fun.

In the Warsaw torture chambers, Yitzhak continued to write poetry, sending the best, as it seemed to him then, for publication in the newspaper “The Voice of the Prisoner”. Then he began to write stories from the life of a thief.

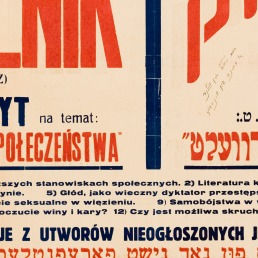

After an unsuccessful release in 1923, Farbarowicz, who “settled” this time in the Rawicz prison, returned to literature. In 1927, he enrolled in a literary studio organized in the prison, already having in his hands about a dozen notebooks covered with stories and verses. At the end of 1929, he felt so confident in the role of a writer that he sent several short stories and the novel “The Love of a Criminal” to the Roy Publishing House.

By the end of 1930, Farbarowicz managed to write thirty chapters of his own biography, but at some point, dissatisfied with the result and annoyed, he grabbed the manuscript and tore it into small pieces. For three months the young writer did not dare to return to a new genre for himself, but soon got down to business with a vengeance. This was facilitated by the acquaintance of the prisoner with the Master of Science Stanislaw Kowalski, a graduate of the Pedagogical Faculty of Poznan University, who in 1930 took the position of teacher of pedagogical disciplines at the teachers' seminary in Rawicz.

Kowalski, interested in the problem of adult education, in 1930 met the governor of the prison and, in exchange for giving lectures to prisoners, received permission to conduct interviews with them.

As a capable prisoner, Yitzhak Farbarowicz was brought to Kowalski for a meeting. The young teacher was amazed not only by the erudition of a man, but also by the fact that he independently established contacts with a popular publishing house, on whose order he was already writing an autobiography. From that moment on, Kowalski took over a kind of patronage over Farbarowicz.

After Nakhalnik completed the first part of his autobiography, covering the period before Poland's independence was restored on November 2, 1918, Kowalski sent the manuscript to the sociologist Florian Znaniecki, then collaborating with Columbia University, and the distinguished psychologist Stefan Blachowski of the University of Poznan. Scientists sent flattering reviews to the book. Following them, Stanislav Kowalski wrote an extensive introduction to the first edition, starting to prepare the book for publication. At the same time, by right of a former legionnaire, a veteran of the war of independence, he addressed a letter to the head of state with a request to release the talented and repentant prisoner ahead of schedule.

In January 1932, Farbarowicz was released from prison. There were problems with work, but he decided to completely quit the criminal world. Having left for Vilna, the imposing man soon married Sarah Kesel, a nurse at the Vilna Jewish hospital. Soon the first part of their autobiography, signed with an unusual pseudonym – “Urke Nakhalnik” – was published.

He pleasantly surprised critics with his extraordinary ability to present the human drama of a prisoner who is rejected by society and therefore quickly returns to the same cell that he recently freed.

The brother of the writer, delighted with the wonderful metamorphosis of the elder Farbarowicz, gave him part of the inheritance.

In addition to literary affairs, Farbarowicz, on a voluntary basis, helped the Yiddish Scientific Institute (Yidischer Wiesenschaftleher Institute, YIVO) in Vilna to compile a lexicographic collection of sayings from the Jewish underworld, suggesting some important additions and corrections for the Hebrew argot dictionary.

The affairs of Urke Nakhalnik continued to go up the hill.

On the eve of World War II, Urke Nakhalnik actively published stories in Polish and Yiddish. It was rumored that some of the thieves' tricks described by Urke Nakhalnik in his stories were adopted by American directors. His story about a specially trained mouse delivering notes between prison cells actually appeared in one of the Hollywood films.

September 1, 1939, the day of the Nazi Germany attack on Poland, the writer met in Otwock. Evacuation to the east was not part of the writer's plans. Farbarowicz decided to act.

When German troops entered Otwock and the atrocities began, Yitzhak Farbarowicz, together with Gershon Randoninski, the son of the owner, from whom the writer rented a villa, decided to repulse the Nazis. Nakhalnik also contacted his good acquaintance, Wolf Nusfeld, the owner of the popular cinema “Oaza”.

They decided to collect explosives and weapons for subsequent acts of sabotage and strike against the invaders and their minions. Nakhalnik and Randoninski found and hid the “firearm” thrown by the Polish soldiers, and Nusfeld buried a box of dynamite in the Sredborovsky forest.

When the rioters set fire to the Goldberg synagogue, Farbarowicz and Randoninski, risking their lives, rushed into the flaming building. Having run through smoke and fire they pulled out the Torah scrolls. At the last moment, the daredevils were able to leave the building, saving the shrines from desecration. The rescued scrolls of Torah Farbarowicz, together with a friend, secretly buried everything in the same Sredborovsky forest, which stretched not far from the writer's villa.

Despite all the precautions taken by the underground, the local hairdresser, the Polish woman Bukoymskaya, whose lover named Mikhailis served in the gendarmerie, learned about the dynamite. Together with the Germans, Mikhailis seized Randoninski, Farbarowicz and Nusfeld, who had weapons found during the search.

After terrible beatings, three of those arrested were forced to dig their own graves in the forest, and then they were shot in cold blood. Thanks to the efforts of the magistrate Otwock, and especially the city doctor, the Germans allowed the exhumation of the bodies a few days later. The families managed to bury the heroes in the Jewish cemetery and even erect monuments to them.

According to an alternative version, the writer died not in 1939, but in 1942. When the Nazis occupied Warsaw, Farbarowicz re-established contact with the underworld and began collecting money and weapons for attacks on the occupiers. In March 1940, Urke Nahalnik, at the head of a group of Jewish “lads”, carried out his first attack on Polish collaborators hired by the Germans to beat up Jews in the streets.

According to Leib Feingold, the leader of the Bundists, Nakhalnik once appeared at a meeting of the leaders of the Jewish underground. Nakhalnik demanded funding for his organization and immediate retaliation against the Nazis. Farbarowicz was refused, after which he returned to Otwock, where he committed acts of sabotage on the train tracks leading to Treblinka, helping Jews escape from trains and hide in nearby forests. Urke Nakhalnik was taken when he untwisted the bolts, which fasten the rails to the sleepers. According to this version, Nakhalnik died while trying to attack the guards, he tried to fight off the convoy when he was taken to execution in the center of Otwock.

Jewish writer Avrom Karpinovich, in his story about the life of Urke Nakhalnik, describes in detail another version of Farbarowicz’s death. When the shackled Nakhalnik and his friends were led along Kosciuszko Street, he contrived and attacked the SS man Schlicht. For this insolence, the arrested were not even taken to the forest, but shot right on the spot.

The fate of the writer's family is unknown. It was only established that his wife and son were transported to the Warsaw ghetto on November 30, 1939, and then their traces are lost.

Yitzhak Farbarowicz lived a rich life. Finding the strength to rise from the very bottom, he became one of the most interesting Jewish writers and defender of his fellow tribesmen, who met in full growth the sworn enemy of his people. In the soul of Urke Nakhalnik, it was not a hardened criminal who spoke, but a deeply religious person who remembered at the end of his life the words of Holy Scripture: “And I will avenge their blood, not yet avenged”.

Urke the Impudent

1897 – 1939