In July 2015, there was a fierce debate in the Warsaw Municipality over candidates for the Honorary Residents of Warsaw. The conservative Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), which had representatives in the city council, openly expressed its discontent: the left decided to nominate Aleksander Kwaśniewski, the former president of the Polish Republic. If there were controversies about the politician accused by the “ruler” of being a secret agent during the years of the Polish People's Republic, then regarding the Israeli citizen Zhuta Hartman both ultra-conservatives and social democrats agreed.

Moreover, it was Polish nationalists who initiated Zhuta Hartman being awarded of the honorary title. “She miraculously survived the revolt and occupation. After the war, she returned to Kielce and witnessed the pogrom. After that, she left Poland forever and never came back here again,” – this is how Marek Makuch, the leader of PiS in the Warsaw City Council, introduced her.

The members of the city council hoped that Zhuta Hartman would come to Poland for the first time in many years to take part in the celebrations. But she refused, because she vowed never to return to “this damned place”. The sons of the heroine, Haim and Yehuda, were awarded the certificate of the Honorary Citizen of the City of Warsaw.

In Israel, about Hartman's heroism was not known for a long time. Therefore, Polish researchers based their information almost exclusively on materials from their own archives.

It all started when the historian August Grabski decided to write about the Jewish Military Union (ZydowskiZwiązekWojskowy, ŻZW) of an underground armed organization of Polish Jews during World War II.

The Jewish Militant Organization (Polish ŻOB, ŻydowskaOrganizacjaBojowa), which consisted of communists, supporters of the Poaley-Zion, Bundists and members of other leftist movements, was covered with glory both in post-war Poland and in Israel, but about the Jewish Military Union, supported by Jewish right-wing organizations, tried not to speak. Politics intervened: the core of the Jewish Military Union was made up of members of three organizations associated with the revisionist movement of Jabotinsky: Beitar, Etzel and Brit HaHayal, which was very disliked neither by the leadership of People's Poland, nor by the functionaries of the Mapai, led by David Ben-Gurion.

For years, a direct participant in those events, Zhuta Hartman, has been vainly trying to convey the truth about the fact that the “revisionists” and former Jewish servicemen fought bravely on the ruins of Warsaw as part of the Jewish Military Union.

Zuta Hartman, née Rothenberg, belonged to a generation born shortly after the restoration of Polish independence and raised in the Second Polish Republic. She was born on October 5, 1922 in the town of Kielce, located at the foot of the Swietokrzyskie Mountains. Zhuta lived there on Mlynarska Street, where she attended primary school and a private Jewish gymnasium for girls.

The family followed Jewish traditions, but the heroine's father, Yehuda Rotenberg, with his wife Bella Eisenberg, Zhuta's mother, preferred to live in the prestigious “Polish” district of the city. The Rotenbergs were a famous family name.

The outbreak of World War II prevented her from passing final exams. Having learned about the sending of Jewish men to labor camps by the Germans, the family decided to urgently send Zhuta’s father to the Soviet Union, where thousands of refugees rushed. Remaining in the city, the Rotenbergs hoped for the prudence of the invaders, but these people in steel helmets were very different from the ordinary Germans, which were enough in Kielce. The misanthropic ideology entered their flesh and blood. In April 1941, all Jews, including the Rotenbergs, were sent to the local ghetto.

Conditions in the ghetto were terrible. Zhuta had to, at her own risk, get out of the barbed wire in search of food for herself, her mother and younger brother. But one day she got caught. A passing Pole ran up to the soldier and indignantly announced that she, a Jewish girl, had gone out of the ghetto without an armband with the blue Star of David.

The German approached Zhuta and demanded documents. But the soldier got distracted by something, and when he stepped aside for the proceedings, Zhuta quickly turned the corner and disappeared into the dense crowd. The girl bought a train ticket from Kielce to Radom, which is halfway from Warsaw. She decided to go to the Polish capital, but it was dangerous to go there without preparation: there were posts and document checks everywhere.

After hiding for some time in the Radom ghetto, Zhuta reached the capital in early 1942. By an underground passage under Leszno Street, she managed to get to the territory of the Warsaw ghetto, where some of her relatives were already.

Zhuta walked along Warsaw street completely alone, until someone called her a nickname that only her friends from Kielce knew: "Zyuta!" The girl turned around and saw a classmate standing on the other side of the road, Abraham Rodal, brother of Leon Rodal.

A classmate smiled: “Zyuta, come with me!” – “Okay”. The girl, who was in the Warsaw ghetto illegally, had absolutely nothing to lose. Together with Abraham, they came directly to the headquarters of the Jewish Military Union on Muranovskaya Square, and Zhuta was immediately assigned to one of the combat cells under the command of Pavel Frenkel from Beitar. The brave Jewish woman immediately began combat training and learned how to use weapons in one of the safe houses on Nalewki Street No. 34, where the sports section of the socialist BUND was located before the war.

“Her people” made Zhuta new documents, and she was able to get a job with her aunt at the Tebens-Schulz textile and fur factory run by a German who hired Jews to work in terrible conditions.

After the Nazis liquidated 300,000 inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto in the Treblinka death camp in the summer of 1942, a group of young Jewish underground fighters created two militant organizations in the ghetto to fight the Germans. The Jewish Military Union was established by the summer of 1942. The founders of the organization were doctor Joseph Zelmeister, journalist Kalmen Mendelssohn, lawyer Mechislav Ettinger, journalist Leon Rodal, psychiatrist David Vdovinsky, Beitarian Pavel Frenkel and officer Mechislav Apfelbaum – basically all of them adhered to revisionist views.

Zhuta was not a member of any political organization, but performed the most important tasks. At first, the underground worker left the ghetto with empty buckets, at the bottom of which were deep bowls positioned upside down. She moved mainly along the sewers running through the entire city. Arriving at the agreed place, she met with messengers who put notes, cartridges, and weapons in buckets and covered them with prepared bowls. A rotten herring was poured from above, exuding a terrible smell.

Going to the surface in the ghetto and bumping into a patrol, Hartman removed the lids of the buckets and calmly presented the contents. The picture was always the same: smelling an unbearable stench, the Nazis, cursing and waving their hands, immediately let go of the girl: “Close it immediately! Go!” As a liaison officer, Zhuta moved from the ghetto to the Aryan side to provide the soldiers with weapons, correspondence and provisions, several times a week.

The weapons were mainly obtained from the little-known small underground organization “Polish People's Movement for Independence”, which was headed by Caesar Shemlei.

One of the leaders of the Jewish Military Union, Pavel Frenkel, vigorously bought weapons through Shemlei, even acquiring machine guns - a rarity for the rebels, who are often forced to use homemade weapons.

It was not scary to walk, because everyone already understood that the liquidation of the ghetto was not far off. A day earlier, a day later - it didn't change anything. The young girl was more frightened by the fact that she would go to slaughter, like a sheep, or, even worse, would not stand the torture and would surrender her comrades. Therefore, in case Zhuta was caught, she always had a cyanide tablet with her.

As Zhuta later recalled, reality was not as beautiful as they write in the books. No one thought about heroism, because there was simply no time for such reasoning.

On April 18, 1943, Pavel Frenkel received a secret report about the imminent start of the German operation and urgently reported this to Mordechai Anilevich, the commandant of the Jewish military organization.

Zhuta Hartman was at that time in the area of the brush factory at 36 Šventoerskaya Street, where a large group of Jews came from the Aryan side to celebrate Passover.

The next day, early in the morning, a large number of SS forces and Ukrainian policemen under the general command of SS Gruppenführer Jurgen Stroop entered the ghetto from the side of Nalewki Street. A fierce battle ensued near the headquarters of the Jewish Military Union. The rebels sat down in the attics and threw grenades from there, responded with rifle and machine-gun fire.

Hartman and her detachment held a defensive position on Šventoerskaya. Zhuta was given a rifle and sent to one of the points on the roof. Seeing the German soldiers, the girl started shooting - the commander ordered her to stand to the last. The Germans opened heavy fire in response, so they constantly had to change positions. On the third day of the fighting, April 21, 1943, Hartman was ordered to go down to the bunker under house number 36 and provide medical assistance to the wounded.4

Zhuta and her brothers in arms understood that death awaited everyone. Nobody planned to surrender. During the battles on Muranowska Square, one of the soldiers on the roof of house No. 7-9 hung out a blue and white cloth and the Polish national flag, well observed from all sides. “We rejoiced for several minutes. Finally we are free!” - Zhuta recalled. The flags fluttered over the ghetto for four days, which the executioner of the Warsaw ghetto Stroop did not forget to write about with undisguised irritation in his report.

They kept on the ruins of houses burned by the Germans for two more days. After the suppression of the uprising, Zhuta and other soldiers took refuge in a well-disguised bunker. Some of them occasionally came out of hiding at night to fetch food and weapons, or to attack the German soldiers who patrolled the ruins at night. But around May 6, the shelter in which Hartmann was located was discovered and blown up by German sappers. After the capture, she was transported to the Umschlagplatz transshipment point, and a few days later she was sent to a camp in Ponyatova near Lublin.

Among the few survivors, she was sent from Ponyatova to the Majdanek concentration camp. In Majdanek, Hartman was punished with 25 lashes for not standing at attention during verification. Moreover, according to her confession, in the camp she was beaten more by Polish capos than by Germans.

Zhuta was sent to forced labor at the HASAG factory, the German arms concern HugoSchneider AG in the Skarzysko-Kamienna camp, from there in 1944 she was transferred to the arms factory at the Buchenwald branch in Leipzig.

Having survived the death march at the end of the war, Zhuta returned with a transport of wounded soldiers to Kielce, where she learned about the death of her father in Uzbekistan and the death of her mother and younger brother in the Treblinka camp. In Kielce, she worked in the local Jewish committee at Planty Street, 7. There she collected information from those who survived the Holocaust, but four months later, even before the notorious pogrom in the city, she and her husband left Poland.

After leaving Kielce, together with her husband Moshe Hartman, whom she met in one of the concentration camps, Zhuta moved first to Germany, then to France, where Zhuta's aunts lived.

Zhuta Hartman immigrated to Israel with her husband and three-year-old son Yehuda in 1952. She was tired of war and agreed to aliyah only after the fighting in Israel came to an end. The Hartmans first lived in Amidar in Bat Yam, and then with several other families from Amidar, most of whom were Holocaust survivors, moved together to the Tel Giborim area in Holon. There they created their own residential complex, where Zhuta's youngest son Haim was born.

After the repatriation, Zhuta tried to convey the truth about the heroism of the “revisionists” and other fighters of the Jewish militant organization. However, her own uncle had strictly warned that Hartman's husband could have problems at work because of the “alternative” information.

In 1961, Hartman, as a victim of the Holocaust, was asked to testify at the Eichmann trial. But right before the trial, she was told that she could not. According to Hartman, she was refused in order to silence the story of the right-wing Zionists who participated in the fighting.

Zhuta was deeply affected by this incident, but did not give up. “It’s hard to strive against fate,” but there was not a single state institution or official body that Hartman did not knock on and demand that they recognize the Jewish Military Union and its merits.

For decades, Zhuta Hartman was systematically denied, and a reference book published by the Lohamei ha-Getaot (Ghetto Fighters) Museum indicated that she died in a concentration camp.

But on the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the State of Israel, a breach was made. In 2008, on the Holocaust Memorial Day, it was Zhuta Hartman who lit the torch of memory. This was followed by the presentation of the Polish title and general recognition at home. In 2011, she participated in an official ceremony at the kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getaot, founded in 1949 by former partisans and Jewish resistance fighters to the Nazis in Poland and Lithuania during World War II.

The last soldier of the Jewish Military Union, Zhuta Hartman, died in Tel Aviv on May 19, 2015, at the age of 92, having completed her task. She left two sons, five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Zhuta Hartman became the prototype of the main character in the documentary film by Yuval Haimovich and Simon Schechter “The Untold Story” (2017).

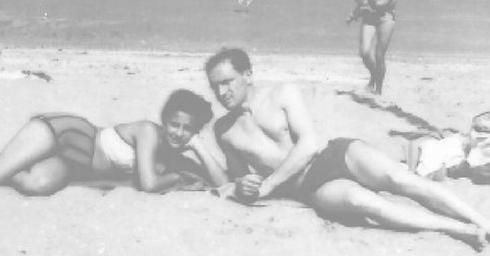

Zhuta Hartman

1922 – 2015