In 1915, the well-known Georgian writer and public figure Yakov Tsintsadze, editor of the newspaper "Samshoblo" ("Homeland"), wrote about the ancient community of Georgian Jews. Acknowledging the Jewish people's desire to return to Zion, Tsintsadze emphasized that the only Georgian Jew "who with all his being serves the restoration of the rights of the much-suffering and oppressed people" was Rabbi David Baazov.

Baazov was, of course, not the only prominent representative of the Jews of Georgia, but his role in the establishment of the Zionist movement in the country, in the cultural and political emancipation of its Jewish community, is truly difficult to overestimate.

The leader of Georgian Jewry, David Baazov, was born in 1883 (according to other sources, in 1881) in the city of Tskhinvali of the Gori district of the Tiflis province, in the family of the local Torah sage Menachem Bazazashvili – a man of deep knowledge respected by all Tskhinvali residents – and housewife Tsipora. The Bazazashvili couple had five children. The "hakham" (sage) Menachem Bazazashvili taught his heirs Hebrew and the holy scriptures himself. It became noticeable in his early childhood that his son David significantly surpassed his peers. Before other boys could learn the prayers, David already knew the entire Pentateuch with commentaries. And when they began to study the Pentateuch, he was already well-versed in the Prophets and Writings.

The Ashkenazi rabbi Abraham Hvoles, who came from Lithuania and served as both spiritual and official rabbi in Tskhinvali, noticed the talented student and, after much persuasion from his father, sent the 13-year-old boy to study Jewish science at the Slutsk Yeshiva, founded in 1897 by Rabbi Yaakov Dovid Wilovsky, known as the Ridvaz. Arriving in the Belarusian town of Slutsk, the boy, who knew not a word of Yiddish or Russian before, very soon not only spoke both languages fluently but also gained a reputation as a very capable student.

It is worth noting that such a biography was extremely rare for Georgia at the end of the 19th century. Local "hakhamim" looked askance at their newly arrived Ashkenazi colleagues; not to mention their attitude towards a teenager who went to study at a "foreign" yeshiva. Another bold move made by David, who became Baazov instead of Bazazashvili in the Northwestern region, was his marriage to a local girl. On May 30, 1903, in the town of Uzda, near Minsk, he married 19-year-old Sorka (Sarah) Movshevna Raskina, a native of Bobruisk. Jewish law had nothing against marriages between Jews from different communities, but the elders of Tskhinvali again began to grumble discontentedly.

But the young Georgian Jew did not stop there. Just as the boy arrived for his studies, the head of the Slutsk yeshiva became Rabbi Isser Zalman Melzer, a friend and admirer of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hacohen Kook, the chief rabbi of Palestine and one of the leaders of religious Zionism. Rabbi Melzer had a very strong influence on David Baazov. Living among his Eastern European counterparts, David clearly saw the weakness of Georgian Jewry. At that time, it lacked the powerful spiritual, educational, and economic institutions that Ashkenazi Jews had, and moreover, it was constantly subjected to assimilation by its Christian neighbors.

The young man set several ambitious goals for himself. Foremost among them was to revive the religious and national sentiments of Georgian Jewry based on the Holy Torah and to do everything possible to elevate its cultural and economic level. And after embracing the positions of the established Zionist movement in the Russian Empire, David Menakhemovich began to believe that the ultimate goal for the Jews of Georgia was to return to the Land of Israel – to the homeland of their ancestors!

After completing his studies in Slutsk, Baazov returned to Georgia, where he immediately began to implement his plans. In 1901, in Kutaisi, he decided to raise funds to organize one of the first Zionist circles among Georgian Jews. He managed to raise 200 rubles for these purposes – a significant amount for those times.

When on August 20, 1901, the first congress of Zionists of the Caucasus was held in Tbilisi, in the theater hall of the former German Club, David Baazov, a delegate from the city of Kareli, was named the most promising propagandist among Georgian Jews. Those present praised the still very young man and asked him to continue the work he had begun so energetically.

The special attention of the congress to Baazov was explained by the fact that although Zionist circles in Georgia had appeared after the First Zionist Congress in Basel, they were exclusively associated with the Ashkenazi community. The Sephardic Georgian Jewry at that time knew practically nothing about Zionism. And the local Jewish clergy, for example, the chief rabbi of Kutaisi and Western Georgia, Ruben Eluashvili, on the contrary, was well aware of Zionism and immediately began an uncompromising war against it.

For some time, David Baazov went back to Lithuania to continue his religious education. In 1903, already with the title of rabbi, he returned to his homeland from Vilnius to serve in the city of Oni in the Kutaisi province. The Jews of this small mountain town immediately realized that Baazov was a representative of a new type of spiritual leader, fundamentally different from the local Torah sages. The young rabbi began his reforms of local Jewish life with a rather radical step: he allowed women into the new synagogue in Oni.

Together with his mentor, Rabbi Hvoles, David Baazov approached the leaders of the Georgian communities with a proposal: based on the experience of Tskhinvali, to open Talmud-Torah and vocational schools in all cities and towns where Jews lived.

This was necessary not only for the cultural and spiritual development of the rising generation but also to detach Jewish teenagers from street trading and give them a good profession that could support a family.

Through Baazov's efforts, a Talmud-Torah was opened in Oni, which, unlike the traditional one, had a modernized curriculum. In it, not only Tanakh was studied but also "Jewish History" by Wolf Javitz; much attention was paid to Hebrew grammar, writing, Mishnah study, and older students studied Gemara with Rashi's commentary. Students attended the Talmud-Torah all day: from morning until noon in Russian, and after a break, in Hebrew. One hundred and twenty children were enrolled in this institution, including those from other cities in Georgia.

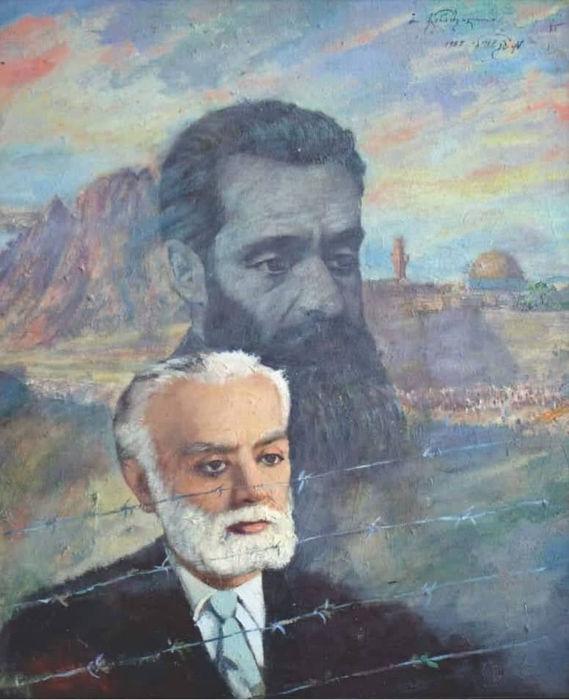

In his fight for the national and religious upbringing of the youth, Baazov named his eldest son, born in October 1904, after the leader of the Zionist movement – Herzl. In one of his articles in the press, David Menakhemovich referred to Theodor Herzl as the founder of the Hasmonean dynasty, who led the revolt against the Greeks, and wrote: "Mattityahu – Herzl, who united life with religion, revived our old hope: 'Nationality and the Land of Israel'."

Despite David Menakhemovich serving in the Sephardic synagogue, and his wife, Sarah Movshevna, praying in the Ashkenazi one, there were no contradictions in the family. For Baazov, all Jews were descendants of one ancient people, and their cultural differences were local color.

During his years of service in Oni, David Baazov became an unquestionable authority not only among the Zionists of Georgia but also in the entire region: he constantly visited Tiflis, Kutaisi, Baku, and Derbent for lectures and speeches. In August 1907, David Baazov, as a representative of the Caucasus, participated in the Eighth Zionist Congress in The Hague, where a number of historical decisions were made. One of them, very important for Baazov, a lover of Hebrew, was to recognize this ancient language as mandatory for Zionists.

In the following year, 1908, on the festival of Shavuot, David Menakhemovich visited Jerusalem for the first time. While familiarizing himself with Eretz-Israel, Rabbi Baazov explored the possibilities of expanding Aliyah – the repatriation of Jews from Georgia. Georgian Jews had begun to immigrate to the Holy Land since 1863, but their numbers in Palestine were still relatively small.

Contemporaries of the Georgian rabbi emphasized that David Baazov had outstanding diplomatic abilities, extremely important for such a volatile region as the Caucasus. In the Hebrew newspaper "Ha-Tzefira," published in Warsaw, on September 14, 1913, it was reported how, after learning Russian literacy, some Georgians read all sorts of nonsense and incitement against Russian Jews in the press, transferring this attitude to the local environment. The situation was exacerbated by pamphlets and brochures published by the "Union of the Russian People," which persistently called for a total boycott of Jewish trade and services.

Once, when Jews from Oni went to sell their goods in villages, they couldn't find a market. They were driven away from everywhere by the local residents, who strictly prohibited them from approaching their settlements. In the villages, the Jews were left with unsold goods, and some had not been paid for previous deliveries. The situation took a serious turn.

Upon learning of the growing abuse, the head of the community hastened to the district chief for a meeting. David Menakhemovich outlined the situation to the high-ranking official, emphasizing that such actions contradicted the laws of the Russian Empire. However, beneath the guise of religion and national sentiments, lay a purely prosaic reason: some people were unwilling to repay debts to Jews. The district chief ordered all bailiffs to immediately cease the lawlessness, and for added persuasion, the elder of the mountain village of Uravi was sent to prison for a week.

The dust settled, but not for long. Soon, another incident occurred in the same village of Uravi. A Jewish merchant visited his acquaintance, who owed him money. The host warmly welcomed the Jew, treated him well, and offered him a place to stay, promising to return the full amount in the morning. However, in the middle of the night, instead of that, the host began to beat the guest and shout loudly on the street: "Quick, quick, Christians, come to help! A Jew has burst in to rape my Christian wife!" Despite the frightened guest managing to escape under the cover of darkness and hide in the forest, the gathered crowd was not deterred, roaming the area and shouting: "Kill the Jew!"

The next day, rumors spread throughout the district that Jews were traveling around the region and assaulting women. Once again, David Baazov managed to uncover the truth: in court, a Georgian gave false testimony. Later, this individual confessed that he was persuaded to do so by others, and his Jewish acquaintance was actually a decent person.

After the February Revolution of 1917, David Baazov served as a rabbi in the city of Akhaltsikhe near the Turkish border. When the city was occupied by Turkish troops and violence against Jews began from their side, Rabbi Baazov directly appealed to the mentor of the Turkish Sultan, Khalid Basha, complaining about the atrocities taking place. The culprits were immediately punished, and the pogroms ceased. According to the memories of Rabbi Emmanuel Davitashvili, in 1918 David Baazov similarly saved 35 Jewish families from the village of Atskveri, who were threatened with either deportation or wholesale extermination.

David Menakhemovich could not remain silent even when in Akhaltsikhe, orchestrated by the Turks and local Muslims, the slaughter of Armenians and Georgians began. The rabbi went to negotiate with the head of the Muslim community of the city, Kazi-Ali-Effendi. Respecting David Baazov greatly, Kazi-Ali-Effendi listened to him and strictly forbade his flock from committing violence against Christians.

Realizing that persuasion and diplomacy alone would not solve the problem, on January 7, 1918, David Baazov participated in a joint council of Georgian Christians and Jews. Measures were discussed at the council to be taken towards their Muslim neighbors in order to avoid future bloodshed in Southern Georgia. It was decided to organize volunteer squads and to establish a joint council of 12-13 people to lead them. Rabbi Baazov became the co-chair of this council, which effectively led the self-defense efforts.

When Georgia entered a fierce political struggle for its self-determination, David Baazov also took an active role. Immediately after the All-Russian Zionist Conference, a conference of Caucasus Zionists took place on August 21, 1917, in Baku. As a member of the presidium, David Menakhemovich delivered a report on the situation of Georgian Jews. He appealed to the conference participants to assist the Jews of Georgia, not only to grant them the opportunity to be full-fledged citizens of the country but also to have the right to study in Hebrew and develop their national culture.

As a representative of Georgian Jews, David Menakhemovich participated in the First National Congress, which elected the National Council of Georgia on November 22, 1917. This council did not recognize the Bolshevik coup and soon became the first parliament of the independent Georgian Democratic Republic.

Due to Baazov's tireless efforts, the village of Oni, where he began his service, turned into a major center of Georgian Zionism. During the years of Georgian independence, a Jewish school operated here, evening courses for studying Hebrew, led by Baazov himself, and a branch of the settlement organization "Hechalutz" consisting of 30 members. Its members were ready to move to Palestine at the first opportunity. In the elections for the Oni city council, the Zionists presented their own list of candidates.

With the assistance of Rabbi Baazov, the most active Zionist committee in the country, the Kutaisi City Zionist Committee, was able to establish Zionist cells in Sujuna, Bandza, and other places. David Baazov regularly spoke to audiences and enrolled new members into Zionist organizations. Thanks to his enthusiasm, new Jewish schools appeared in the country, and more and more people were learning trades and engaging in cultural initiatives.

However, all of Rabbi Baazov's activities, whether cultural, religious, or political, continued to encounter fierce resistance from the Georgian Jewish community, which united around the organization "Agudat Israel" in 1917.

Starting in 1918, when the Zionist Organization of Georgia published the newspaper "Voice of the Jew," David Baazov and the newspaper's editor, Shlomo Tsitsiashvili, obstructed "Agudat Israel" so much that they were subjected to a religious anathema known as "herem." A memorandum was submitted to the Georgian government requesting the closure of the newspaper, and the publication encountered problems. Only the assistance of the district committee of the Caucasian Zionist Organization helped rectify the situation.

In his written works, noting the low cultural level of Georgia's Jews and the need to lift them out of this lamentable condition, Baazov engaged in polemics with the rabbis of Kutaisi—according to him, they were the ones keeping the Jews in the darkness of ignorance.

Another uncompromising force opposing Baazov were certain Georgian public figures who viewed the local Jewish community not as a separate people but merely as a religious sect within the unified Georgian nation. This view was shared by the ideologue of Jewish assimilation, Mikhako Khananashvili, who criticized Baazov for his enthusiasm for ideas that, from his perspective, were natural in Warsaw and Odessa but not in Tbilisi.

The progress of the Zionist movement in Georgia came to a halt due to the annexation of the self-declared independent state by Bolshevik Russia. From February 1921, the Red Army began its invasion of Georgia, and in March 1922, Georgia became part of the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. The population gradually had to forget about political freedoms.

Initially, the Communists preferred not to disturb the Jews: in Jewish schools founded by Zionists, Hebrew instruction was even retained, and a number of Jewish cultural and educational institutions were opened, similar to those existing for other non-titular nations. However, after the suppression of the anti-Soviet uprising in Georgia in 1924, persecution began for Zionist activities. In 1924, after the publication of three issues, the authorities closed the last Jewish-Georgian newspaper "Makaveeli," published by David Baazov and another prominent Georgian Zionist, Nathan Eliashvili.

The leaders of Georgian Zionists had to work under very harsh conditions. Nevertheless, they constantly maintained close ties with Russian and foreign Zionist organizations and tried to find common ground with the Georgian party leadership.

One success was undeniable. In May 1925, the newspaper "Haaretz" reported that David Baazov had managed to persuade the Soviet leadership to release 300 Jewish families from Georgia to Eretz-Israel. Jews were granted permission to leave due to their landlessness and desperate economic situation.

Here's how it happened: David Baazov and his associate Eliashvili first asked the party leadership to allocate land to Jews who had become impoverished as a result of the economic policies implemented by the Soviet authorities. As expected, their request was denied, but they were officially sent to Palestine to explore the possibility of obtaining land there for the "extremely destitute part of the religious Georgian Jews." A special government commission was appointed by the highest Soviet and party bodies, headed by Sergo Ordzhonikidze. It also included Vano Sturua, Mikha Tskhakaya, and David Baazov himself.

In May 1925, Baazov arrived in Tel Aviv, where he met with old friends – Chaim Weizmann, Menachem Ussishkin, Nahum Sokolow – who helped obtain certificates for the entry of Georgian families into Eretz-Israel from the then ruler of Mandatory Palestine, Governor-General Herbert Samuel. At the same time, Baazov negotiated with the Jewish National Fund ("Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael"), from which he expected financing for the purchase of land plots for at least half of the newcomers.

During his visit, David Baazov addressed the residents of Tel Aviv at the "Beit Ha'am" venue. At the event chaired by Joseph Klausner, the rabbi was recommended as the "head of the Zionist Federation of Georgian Jews." Before the Tel Aviv audience, Baazov delivered a report on the political, economic, and cultural situation of the Jews in Georgia.

Upon his return to Georgia with the certificates, David Menakhemovich sent the first group of eighteen families to Eretz-Israel in October 1925. Leading this group was Nathan Eliashvili. Baazov also planned to go to Palestine with his family, but the authorities set such tight deadlines for departure that he was unable to do so. The Baazov family, including three sons – Hertzel, Chaim, and Meir – and a daughter, Faina, were expecting another child. The departure was scheduled just when Sarah Movshevna was in the maternity hospital with her newborn daughter Polina. Baazov's dream of Zion did not come true. Soon after, the plan to resettle Georgian families in the territory of the British Mandate was abolished.

Although David Menakhemovich did not make it to Palestine, he had no intention of ending his Zionist activities. As his daughter wrote, the family knew well that their father, while in various cities, primarily in Moscow, continued to maintain contacts and meet with surviving Zionists in the USSR. This primarily concerned the so-called "United Center of Zionist Organizations in the USSR," operating in Moscow.

The NKVD had information that in the middle of the summer of 1934, underground activists gathered at the "National" hotel in Moscow to discuss the future of the Zionist movement in the USSR. In addition to David Baazov, who came from Georgia, the meeting was attended by: one of the leaders of Moscow Zionists, Joseph Kaminsky, the chairman of the "center" Victor Kugel, Jewish writer Avraham Kari, religious Jew Boris Deksler, and a certain "Sasha" Gordon.

At the Zionist underground meeting, they discussed Boris Deksler's trip to the communities in Ukraine, convening a general Zionist congress, and expanding active underground work.

Writer Avraham Kariv, who participated in the meeting and moved to Palestine at the end of 1934, recalled how he specifically went to see the chairman of the Jewish National Fund, Ussishkin, to convey greetings from David Baazov. Perhaps in this way, Baazov attempted to restore lost contact with the leadership of the Jewish community in Palestine. However, this attempt was in vain: in the autumn of 1934, the underground center was crushed. Victor Kugel, Joseph Kaminsky, and Boris Deksler were arrested, and there were arrests among the Leningrad Zionists associated with the "center." Only Gordon remained free—his real name was not Alexander but Grigory—a NKVD agent.

David Menakhemovich remained at large for a while. Although he was warned of the danger, he continued to visit houses where provocateurs appeared. But in April 1938, Baazov's eldest son, Hertzel, was arrested. A convinced Zionist from childhood, Hertzel Baazov, who by that time headed the dramatic section of the Union of Writers of the Georgian SSR, was accused of nationalist agitation for the resettlement of Jews to Palestine and espionage in favor of England.

Suffering from heart disease for the past decade, David Baazov was admitted to the hospital with a severe attack. No sooner had David Menakhemovich been discharged from the hospital than both he and his middle son, Chaim, a lawyer by profession, were arrested by the NKVD.

The case under Articles 58-10 and 58-11 of the Criminal Code of Georgia was a group one. In addition to father and son Baazov, those implicated included: former head of the Georgian organization "Keren ha-Yesod" Dr. Ramendik, former member of "Tseirei Zion" and director of the 103rd school mathematician Paikin, Dr. Goldberg, former authorized representative of the Foreign Trade of the USSR for the Transcaucasus Eligulashvili, and junior research fellow at the Historical-Ethnographic Museum of the Jews of Georgia Chachashvili.

At the time of his arrest, the former leader of the Georgian Zionists served in the city of Gori in an inconspicuous administrative position. The indictment against David Baazov stated that since 1904, he had been closely associated with the "leaders of world Zionism."

Regarding his visit to Palestine in 1925, it was alleged that by deceiving the government, which allowed him to go there to clarify the issue of obtaining land for needy Georgian Jews, he "resumed his criminal connections with the leaders of world Zionism, with their help obtaining hundreds of certificates."

The indictment also mentioned his active membership in the underground Zionist organization "up to the liquidation of this criminal hotbed and the arrest of its members, enemies of the people: Kugel, Kaminsky, Bernstein, and others." It also stated David Baazov's connection with Rosen, a representative of "Agro-Joint" in Moscow, to whom he allegedly passed on espionage information.

Chaim Davidovich Baazov was accused of joining the underground anti-Soviet organization of young Zionists "Tseirei Zion," founded by his brother Herzl in the early twenties.

For eight months, Sarah Movshevna Baazova waited in queues at the NKVD reception, invariably receiving the same response: "The investigation is ongoing." No personal belongings or food parcels were allowed. Only 75 rubles per month per detainee were accepted. Later it became known that the NKVD officers kept the money for themselves, condemning Baazov and his sons to a blatantly impoverished existence in the dungeons.

During the "radical upheavals," as they called the arrest of Yezhov and Beria's transfer to Moscow, the case of David and Chaim Baazov was transferred to the Supreme Court of Georgia. The hearings were scheduled for March 23, 1939.

None of the defendants admitted guilt to the charges brought against them. When the judge asked David Baazov why he didn't prevent the Jews who moved to Palestine in 1925 from leaving Georgia, the accused's response was categorical: "We tried, we asked for land. But there was no free land then. People's Commissar of Agriculture Sasha Gegechkari sarcastically replied to my demands that if the Black Sea dries up, then they could allocate land to the Jews."

No matter what tricks the prosecution and the clearly biased judge used, nothing helped: David Baazov's sharp mind, his knowledge of the law, demolished opponents' arguments.

"I draw the attention of the High Court to how cornered defendant David Baazov wriggles," shouted the prosecutor. "No wonder the enemy, with the help of enemies, deceived the Georgian government and achieved the organization of the emigration of Georgian Jews to Palestine."

Equally loudly, David Menakhemovich cornered the prosecution: "Wrong! I declare that all my activities during those years, what you call a crime against Soviet power, were carried out not with the help of enemies of the people, but in accordance with the decisions of the government commission led by Sergo Ordzhonikidze." To corroborate the truthfulness of his testimony, Baazov filed a motion and categorically demanded to attach the necessary government documents to his case. The prosecutor became hoarse from shouting, but legally he couldn't do anything: David Baazov was right!

For such audacity, in April 1939, David Menakhemovich Baazov was sentenced to death. His son, Khaim Baazov, for non-reporting, under Article 58-12 of the Criminal Code of Georgia, was sentenced to five years of imprisonment.

However, the battle against the repression machine was not yet lost. Baazov's daughter, Faina, hired the renowned Moscow lawyer Ilya Braude, who was horrified by the poorly constructed accusation and immediately filed a complaint with the Supreme Court. As a result, by the decision of the Judicial Collegium on Criminal Cases of the Supreme Court of the USSR, the verdict of the Supreme Court of the Georgian SSR dated April 2, 1939, was overturned, and the case was sent for additional investigation.

This time, the case did not go to court but was considered by the "troika" of the USSR Ministry of State Security (MGB) in Moscow. Eventually, almost all the defendants in the case were released from custody. In March 1940, Chaim Baazov was released. While still in Tbilisi prison, he learned that his father had been sentenced to a relatively mild punishment – exile to Siberia. The elderly Zionist was sent to the village of Bolshaya Murta in the Krasnoyarsk Region. A year later, on the eve of the Great Patriotic War, David Menakhemovich's wife came to join him in exile.

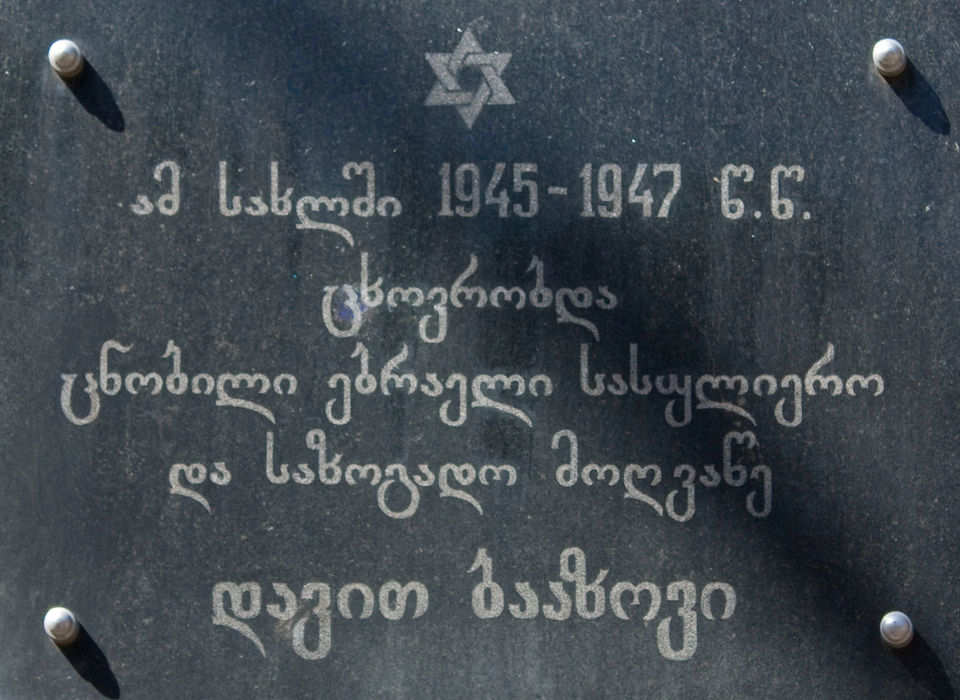

In 1945, the Baazov family returned from Siberia. In Georgia, David Menakhemovich resumed his public activities: he participated in mourning rallies in memory of the war victims, organized aid for soldiers wounded on the fronts, and always tried to find words of comfort and encouragement for his former parishioners. However, David Menakhemovich never fully recovered from the loss of his beloved son, Hertzl, who was executed in August 1938 in the Tbilisi internal prison of the NKVD.

Rabbi David Baazov, the outstanding leader of Georgian Zionists, passed away on October 17, 1947.

Two years later, his younger son, Meir Baazov, was arrested in a case involving an "anti-Soviet group," which also included Zvi Preigerzon, Zvi Plotkin, and Itzhak Kaganov. Their "crime" consisted only of their enthusiasm for Hebrew and an attempt to send their works to Israel. They were instigated into this reckless act by the same "Sasha" Gordon, who once worked on the case of the underground "center." After the war, this scoundrel, well acquainted with the elder Baazov but unknown to his younger son, was organizing variety concerts while simultaneously identifying Zionists in the intellectual circles.

Only David Menakhemovich's daughters, Faina and Polina Baazov, managed to fulfill his great endeavor: in 1973, they repatriated to Israel.

Rabbi David Baazov is honored both in Israel and in Georgia. A museum of the history and ethnography of Georgian Jews in Tbilisi, as well as streets in Oni and Jerusalem, are named after him. His memory is blessed!

30.07.2022

David Baazov

1883 – 1947